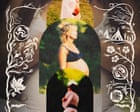

With the Family Stone, Sly was so audacious it was hard to believe his brilliance could ever be exhausted – making his unravelling all the more painful to watch

Even though he recorded three of funk’s most foundational albums – four if you include 1970’s Greatest Hits, as flawless a good time as pop ever delivered – Sly Stone’s subsequent fall from grace was perceived as a grave betrayal of his talent. That Stone’s unravelling was so conspicuous – his drug abuse apparent in every wasted chat show appearance, his infallible hit-machine waning after his Family Stone became estranged – only exacerbated the sting of this loss. But Stone’s imperial era lasted almost a decade and delivered a discography that remains the acme of funk. He changed the course of pop and reconfigured the structure and essence of dance music, multiple times. He was an icon of hope, of pain, of pride. He was Icarus, for sure. But when it mattered, boy did he fly.

On arrival, his brilliance was so audacious it was hard to believe it could ever be exhausted. He seemed to tease this himself on 1968’s Life, promising, “You don’t have to come down!” Perhaps this confidence sprang from his knowledge that he’d already stumbled before he’d soared. The Family Stone’s 1967 debut album, A Whole New Thing – restlessly and inventively mashing psychedelia, soul, funk and rock into, well, a whole new thing – had been too much too soon, and baffled audiences. But the following year’s Dance to the Music simplified the formula and brought new focus, its title track and the 12-minute Dance to the Medley sounding a call to funk the world couldn’t resist.